Five Lessons From [another] Failed HealthTech Startup

Despite great promise, we had to shut down our dementia startup, Veronica Health

tl;dr

Late in 2024, our team had to shut down our dementia startup, Veronica Health. My best life learnings have come from failure, so I thought it might help to share 5 key lessons that may help entrepreneurs innovating at the intersection of value based payment and specialty care and dementia more specifically.

My reintroduction to dementia in 2023

When I joined Oxeon in the fall of 2023 after a sabbatical in Spain and over 15 years as an operator, I was excited to help lead a platform that offered the chance to create a much larger portfolio of impact on health care. And importantly - help the Oxeon team bring to market a dementia value-based care business they had been incubating.

Dementia is a devastating illness. Feared by families more than any other diagnosis, the direct and indirect costs of dementia are estimated to quickly eclipse $1 trillion in the next few years. I saw it firsthand.

Personally, my grandmother lived with dementia during the last few years of her long and wonderful life. Hers was a diagnosis of vascular dementia, and thankfully by the time symptoms were significant, she was living safely in a nursing home. That said, my mom and her siblings were responsible for the innumerate non-medical caregiving issues that you would expect. Bills, scammers, insurance, the house, etc. It was a lot and emotionally difficult. But there was also the clinical complexity that the nursing home was not equipped to handle. The medical system seemed to treat my grandmother as if the dementia was nonexistent. For example, at the age of 95, my grandmother’s doctor recommended that she have a mammogram. My mom had to remind the doctors that perhaps a diagnostic test for breast cancer was not the best step for a blind, demented 95 year old lady whose family wanted her to live out her life in comfort as much as possible.

Looking back it strikes me now that my mom played a unique, dual role overseeing clinical and navigational support. This was only possible because she was a nurse practitioner - she could facilitate the logistical family matters and also anticipate and triage serious clinical risks. I believe that everyone living with dementia deserves this experience/support. Interestingly enough, peer-reviewed literature shows that it works. The most well known model is UCSF’s “Care Ecosystem” program. This evidenced based model was the inspiration for Veronica’s approach: hands on, clinically & logistically interwoven, and deeply connected with primary care and the patients other doctors.

Professionally, I encountered the other side of the dementia problem several times during my career. When I was building Cohere Health with Humana, Humana’s then-CEO Bruce Broussard named dementia as one of the two biggest clinical challenges facing the insurer over the next decade (in addition to obesity). At Oxeon, friend-of-the-firm Paul Kusserow named dementia the next wave of chronic illness for our country in his book, The Coming Revolution, 10 Forces that Cure America’s Health Crisis. And at Iora Health, I saw firsthand the difficulty our primary care physicians faced caring for patients and their families living with dementia. When we pivoted Iora Health into Medicare in 2014, we made a distinct effort to hire geriatricians who were among the best in their field at diagnosing and caring for patients and families living with dementia. Yet despite these amazing doctors, the pathways and playbooks they brought into Iora, and all the advantages of the Iora model (technology, expanded team, and longer visit times), Iora was not successful in achieving our goals with our dementia patients. Diagnosis rates from doctor to doctor and clinic to clinic varied by more than 3x, as did the consistency of support we offered. Meanwhile our physicians felt disempowered and demoralized, which contributing to our physician retention challenges.

Enter Veronica

Oxeon began working on a concept in dementia in late 2022 after the investment team deduced a pattern from insights derived from its proprietary talent network: clinical and business leaders from the Home-Based Primary Care, Personal Care Aid, and Medicare Advantage industries all reinforced the need to address a large and growing problem. Interestingly, the business model also looked attractive. In mid-2023, CMMI then announced a new payment model, a validating signal relevant to MA plans focused on their core customer. When I joined in September I was excited about the prospect of a focused dementia specialist value-based provider offering addressing a deeply personal problem, but I was skeptical given my observations building and running value-based technology enabled services companies in both primary and specialty care:

Achieving attractive unit economics at scale is very difficult and capital intensive

It takes at least twice as long as you would think for MA plans to adopt a new payment model and you must believe that the health plan will prioritize putting resources to develop the payment model

The fundraising environment in 2024 was under significant pressure

It is challenging to differentiate once the payment model is established

CMMI payment models do not guarantee success

To be confident we could mitigate these issues, we believed we needed to prove the following:

Private insurance plans, beginning with MA plans, would create/fund value-based models for dementia

MA plans and risk-bearing PCPs would carve out budgets as soon as 2025 to pay in a value-based construct

We could build a differentiated clinical model that could generate the clinical and other outcomes necessary to show efficacy and differentiation

We could hire a world class team that was purpose built to achieve these results

With Oxeon behind us, I was confident in #4. To my somewhat surprise, we were also able to prove the first three fairly rapidly. With the commercial and operational momentum, we made the recommendation to Oxeon’s Board to raise institutional capital and I leaned in to be co-founder & CEO. All we needed next was a name. Thanks to a nudge from my friend Andrew Schutzbank, we named Veronica Health after Elvis Costello’s hit song about his grandmother with dementia.

Exit Veronica

Fast forward to the fall of 2024, we were not able to close the financing necessary to capitalize the business. This meant that after 18 months of work, more than $1.5m invested, and high expectations from investors, partners, employees, community stakeholders and service providers, we made the difficult decision to shut Veronica down. We didn’t even have the chance to get our v1.0 website off the ground and fix the original logo (the forget-me-not flower is associated with Alzheimer’s disease).

5 Lessons of the Veronica Health failure

Through the failure, my hope is that others can learn from our challenges. Five lessons that stuck out as particularly relevant for those evaluating specialty value-based models, including dementia, in today’s environment.

You can speed up MA plan go-to-market by starting with full-risk PCPs

Demonstrating clinical excellence is table stakes

Fundraising is hard - even when you have impressive customer traction

Dementia is a challenging nut to crack, but I think we were onto something

Timing a new CMMI payment model well does not guarantee success

1 - Speeding up MA plan go-to-market by starting with full-risk PCPs

Many entrepreneurs struggle to make traction selling to Medicare Advantage (MA) plans. Even for projects with established budgets, mature service providers can expect 18+ month sales cycles. For startups with no track record, it is harder/longer. That being said, at Veronica we had an insight that we could establish a beachhead with the most progressive MA plans with a carefully conceived go-to-market strategy. This strategy revolved around signing FFS contracts with MA plans, but completely orienting the model to support full risk PCPs - arguably the most important partners to the MA plans.

First, we operated as a provider organization, and not as a care management program. This meant low barriers to get started in a fee-for-service (FFS) contract with those health plans that we identified as early priority. This would allow Veronica to build an early track record and refine the model, but more importantly supply us with powerful stories of how we were impacting members of those target MA plans. Encouragingly, this approach was economically more viable than other specialities like primary care. We estimated that even with fee-for-service rates, our clinical model could generate a small margin.

Second, we contracted directly with the MA plans’ most important risk-bearing PCP partners. Already in network with the MA plans as a “specialist” treating patients and caregivers living with dementia, Veronica would then be able to integrate those services into the workflow of PCPs and be compensated with value-based reimbursement. This was more of a clinical model decision than business model - our core hypothesis was that dementia care and support would be most impactfully delivered when deeply integrated into primary care.

Other factors honed our focus on risk-bearing PCPs.

Of all the stakeholders in the healthcare system, risk-bearing PCPs are the most financially, clinically and operationally burdened by patients and caregivers living with dementia

Risk-bearing PCPs have disproportionately larger panels of MA plan members relative to other patients populations

Risk-bearing PCPs are important partners of the MA plans, and they are often consulted by the MA plan before the plan makes a decision to pursue a risk contract with a value-based specialty care provider

By the time we closed down the company, Veronica was at the contract signing stage with one of the largest full-risk primary care groups in the country, in one of the largest MA metro areas in the US. Another, even larger PCP group was not far behing. This traction played a large role in influencing two of the largest MA plans in the country to launch formal procurement processes with Veronica before we had even seen a single patient.

2 - Demonstrating clinical excellence is table stakes

One of the moments that gave me confidence that Veronica could achieve its potential was when my friend and former colleague from Iora, Dr. Carroll Haymon, MD agreed to join as co-founder & Chief Medical Officer. Carroll is a family doctor and earned her fellowship in Geriatrics from Swedish Health in Seattle, one of the pre-eminent clinical institutions in the US. Her entire clinical career has been in the study and service of older adults, and she honed a passion for handling challenging and common ailments that affect all of us as we age, including dementia. At Iora she brought her dementia perspective and leadership into the teams, practices and markets she ran, and by the time Iora was acquired by One Medical, she was responsible for Iora’s nationwide provider development program, of which dementia care and support was one of three core elements.

Carroll is not a prototypical sales-oriented startup CMO. That said, when Carroll and I went and met with MA plans and risk-bearing PCPs, guess who did most of the talking about Veronica’s point of view on dementia and what works? These organizations get pitched every single day, and the easiest way to dismiss an idea is if the clinical grounding is not proven or compelling. As I learned from a business school marketing professor, clinical excellence is a “hygiene factor” to an MA plan not unlike how a consumer views a clean bathroom in a fancy restaurant. You don’t try a high end restaurant because you hear the bathrooms are spotless, but if they are not, you will never go again. One of the first chores my dad taught me as a kid was to clean bathrooms, and you can bet Veronica’s bathrooms were spotless.

For example, I had a strong relationship with the Chief Quality Officer of one of the most prestigious “pay-vidors” in the US. When I asked for a meeting, that leader suggested that Carroll meet 1v1 with the medical director in charge of geriatrics before considering next steps. Veronica did not have any operating experience to demonstrate results, however Carroll’s humility, storytelling, and experience combined with the rigor with which we applied the evidence from programs like UCSF’s Care Ecosystem program gave such leaders confidence we were a partner on which it was worth making a bet. We recognized that we had earned early trust, but would need to deliver against it. As a result, we made “clinical excellence” one the company’s core values.

3 - Fundraising is hard - even when you have impressive commercial traction

CEOs from 3 different dementia companies reached out to me since we shut down Veronica. One of them asked a very direct multi-million dollar question.

“Duncan, you have a lot of experience in value-based care, it sounds like you built a differentiated model, had unmatched customer traction, and you seem to have built a dream team. So what happened?”

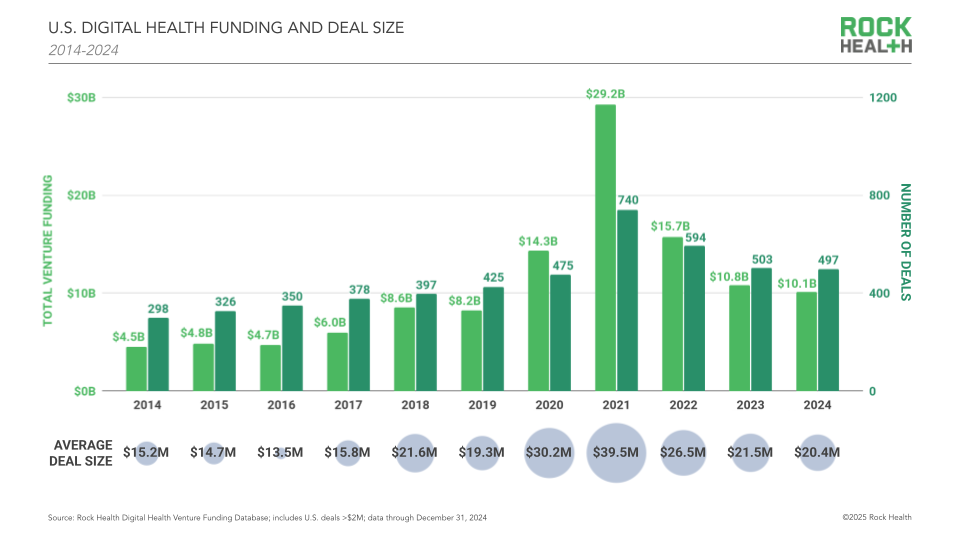

Ouch. The simple answer is that the fundraising environment for technology enabled VBC services companies was about as hard as it has been in 10 years. Healthcare venture funding feel precipitously since the zero-interest-rate boom a few years back, and the activity was even more depressed for non AI-native companies.

But the more complex answer is that there were two core drivers that inhibited our ability to raise capital.

First, we didn’t do ourselves any favors with our financing strategy. We believed the right way to build the business was to raise $9m+ in institutional funding led by 2 lifecycle investors. This funding from this caliber of investor would allow us to hire the early on-the-ground teams in our first market, start taking care of patients and their caregivers in partnership with our PCP partner, demonstrate early outcomes, build out the early product team and facilitate the process to close contracts with 2 large MA plans. This would be a big round, but we felt that these milestones were key to raising the next round of financing. Not only did the size of the round add challenges, our available pipeline of funds was small. The list of lifecycle funds investing in value-based tech-enabled services businesses is even fewer when you filter out those VCs who were invested in competing businesses.

Second, this was the first time I raised capital and I made a lot of mistakes. Those included:

We were not clear on my role as CEO early on when we were floating the concept with VCs before we formally started the fundraising process. This caused some confusion/doubt about my role.

We signed a term sheet relatively quickly in the process. This was a great offer from a top quartile fund with an investor I deeply respected. But we slowed down our pace of engagement with the market in the days that followed. I assumed other funds would fast follow, and I was too cautious about deferring to our lead investor. Time slipped.

I consider myself to be a strong salesperson, but fundraising is very different from complex solution selling. The process engineers self-doubt as it is very difficult to understand where you stand in the VC’s process, and VCs are rarely direct in their intentions/interests - even when you know them well personally.

The self-doubt wore down on my confidence, and I did not sell the vision as well as I could have/should have. A mentor of mine likes to tell me that I should “fake-it-till-you-make-it” more. I actually don’t agree with faking it, but I do appreciate that VCs are making a big bet on an exciting future, and if the CEO can’t articulate why that future is so compelling, it makes it harder to cut a check.

Raising money is all about driving momentum in the market. When it was clear that we were losing momentum after signing the term sheet, we should have been proactive with our investor to discuss whether we should make the terms more attractive.

4 - Dementia is a hard nut to crack, but an area where we are desperate for innovation

If VBC is a difficult area, dementia VBC is harder. Challenges relate to all aspects of building a company: attracting patients, clinically intervening, and value-based contracting.

Attracting patients is hard

Most people don’t actually want to confront the prospect of a dementia diagnosis - this makes patient acquisition difficult, particularly in early disease when there is the biggest chance of long-term impact.

Often family members are motivated to help a loved one get help, but in some cultures this is not true. In these cultures, dementia is often considered a part of normal aging and it is a taboo subject.

Clinical intervention is hard

The disease is fatal, there are no cures, and new treatments that delay progression of the disease have efficacy that is questioned by physicians.. This makes diagnosis a difficult prospect for providers who can’t really help the patient and family

The jobs-to-be-done in dementia treatment is support. A lot of the support is for the family, and family support is not reimbursed. Support also doesn’t sound very science driven, even if the evidences is strong.

While published studies like those at Ochsner show that telehealth can have a big impact, it is hard to argue that a virtual-only solution can provide the level of care and support that patients and families need. The studies from UCSF, Ochsner and elsewhere also had strong in-person connections with their PCPs and specialists. We were convinced we needed a local market solution, and in-person components become costly.

Many of the most challenging issues in dementia: housing, access to in-home caregiving, etc are never going to be met by a dementia VBC company like Veronica.

VBC contracting is hard

Health plans don’t fully understand the total cost of their dementia population. If you asked an MA plan P&L leader where dementia ranks by cost on their clinical dashboards, they would not be able to tell you. They would be able to tell you where musculoskeletal care, cardiovascular care, and cancer care stack rank. Neurology claims are not even on the page. Dementia’s “invisibility” in the data exists because the costs of dementia manifest in claims related to chronic and behavioral issues that are exacerbated by the disease. A heart failure patient with dementia is never admitted to the hospital because of her dementia, she is admitted because she was unable to manage her complex medication regimen for her heart failure.

Attribution of impact requires sophisticated analytical rigor. If a dementia intervention is improving outcomes that in theory should be addressed in primary care or cardiology, what is to say that the dementia organization will get credit?

One of the big reasons MA plans are watching the space is that the emerging therapeutics are very expensive pressuring already-thin margins. While scripts are growing quickly, the pace of the infusions is much slower than analysts predicted. The stock price of Eisai, whose drug Leqembi was the first approved to treat early stage Alzheimer's disease, gives hints about where scripts are relative to expectations.

Like all VBC businesses, demonstrating time to value is harder than AI upcoding, and data access is getting more challenging post the Change Healthcare hack.

Veronica partnered with a major actuarial firm to demonstrate how our intervention could credibly drive total cost of care improvement for MA members we diagnosed with dementia.

That said, unless you are focusing on later stage disease, the medical cost improvement opportunity in dementia takes years to demonstrate on a population level. Individuals with early stage dementia do not generate significant medical claims.

It is difficult to claim impact for those in later stage disease given the core intervention (end of life planning) takes so much trust and time.

At Veronica, one key insight we had was to target individuals with early stage disease. We did this because we saw the opportunity to improve accurate diagnosis of dementia. Dementia is underdiagnosed at rates of more than 50%, and the lack of a diagnosis limits the opportunity for an effective treatment plan. By establishing trust with the patient and family early in their dementia journey, it offered the opportunity to make a big impact on a 10-20 year health journey. Equally if not more importantly, the dementia HCC code was not affected by CMS’ v.28 risk adjustment changes, which meant that Veronica could increase revenue for MA plans and the PCP groups who contract for risk.

Credibly addressing the risk adjustment opportunity is difficult given the scrutiny MA plans are under by regulators.

5 - A CMMI Model is not a guarantee

In recent years several waves of startups were born out of CMMI payment models, including primary care designs like MSSP and ACO Reach, as well as kidney care designs like CKCC.

While several exciting companies have enjoyed success as a result of early anticipation of these models, what has become clear is that these models were not the core driver of their success. Typically there were other forces in the market, and notably all relate to innovation in the private insurance market (namely MA). In primary care, MA plans had been working in full-risk contracts for more than 5 years prior to MSSP and ACO Reach, and in kidney care one of the key changes to the industry was when CMS allowed Medicare Advantage plans to enroll members with ESRD.

The model track record out of CMMI is mixed, with some programs generating significant savings (like MSSP), and others not.

CMMI models invite competition, particularly when there were low barriers to entry to getting a CMMI/CMS contract. To some extent this is the goal: CMMI capital accelerates model scale, but when service providers are fighting over the same patients or providers, the economic opportunity can be fleating.

When GUIDE was released in 2023, it was (appropriately) viewed as a huge validation of the problem given the government and taxpayers are the main payers of dementia’s cost.

However, the barriers to getting a GUIDE contract were lower than any prior model released by the agency. Hundreds of organizations were accepted into the program. This flooded the market with different point solutions tackling different aspects of the dementia problem.

Additionally, close analysis of the program shows that GUIDE was not underwritten to achieve any savings. With the changeover in the Administration, this exposed the model to scrutiny.

At Veronica, we were wary of these risks and underwrote our business plan to assume that 80%+ of our revenues would come from MA plans vs. GUIDE, and that the true opportunity was with MA plans and other insurers as testing costs creeped into younger populations.

Conclusion & advice

Despite all the challenges we encountered, I am confident that Veronica could have been successful and I am bullish on the opportunity to bring value-based care to dementia. The problem is at crisis-level and accelerating, the market opportunity is massive, health plans and PCPs have established budgets to tackle the problem, there are evidence based models that demonstrate impact, and the issue hits every boardroom around the country. And this is not just a hypothesis - in the last four months, 3 health plans and 2 risk-bearing PCPs have asked me for help with their dementia strategy.

Each of these organizations asked for my advice, which made me think of what I would do if I took another crack at dementia.

Build the model from the evidence of the Care Ecosystem. Embrace the benefit of virtual care, but remember that the trust building necessary to make a diagnosis and support the family takes some in-person/community presence.

Aggressively use AI to think about how to solve for the inherent labor challenges that exist in what needs to be a high touch model in person and virtual.

Make a decision on what part of the dementia pathway to focus. Early stage seems to be where the greatest long term impacts (and largest lifecycle savings) are, and also where there is an opportunity to show immediate value with risk-bearing entities (PCPs and plans).

Rather than compete with primary care, deeply integrate with PCP groups and in PCP workflow. However, ensure the solution is always 5x better than what primary care could do themselves. Iterate quickly and always be thinking about whether a pivot will be necessary to offer technology/services to PCPs as opposed to being a full-service specialist.

Partner with one of the top 3 hospitals in the first launch market - be their access solution to their dementia problem facing their neurology service lines. This will be a big unlock for patient acquisition and maybe even something the system will pay for.

Try to build the team in person and ideally as close to the initial launch market.

Keep the company focused on what is in the best interest of the patient/caregiver and those who help them. Done well, and particularly augmented with AI, there is a chance to build high-touch service-as-software that can also be a great business.

If this is helpful for those who are innovating in dementia or value-based care more broadly, fantastic. We need more and faster progress, and I am happy to help.

Duncan,

Thank you for this very thoughtful article. Appreciate your honesty and generosity.

Mary

Love the insights/determination. 100% agree that you have to learn from failure(s).